So Long, Frank O. Gehry

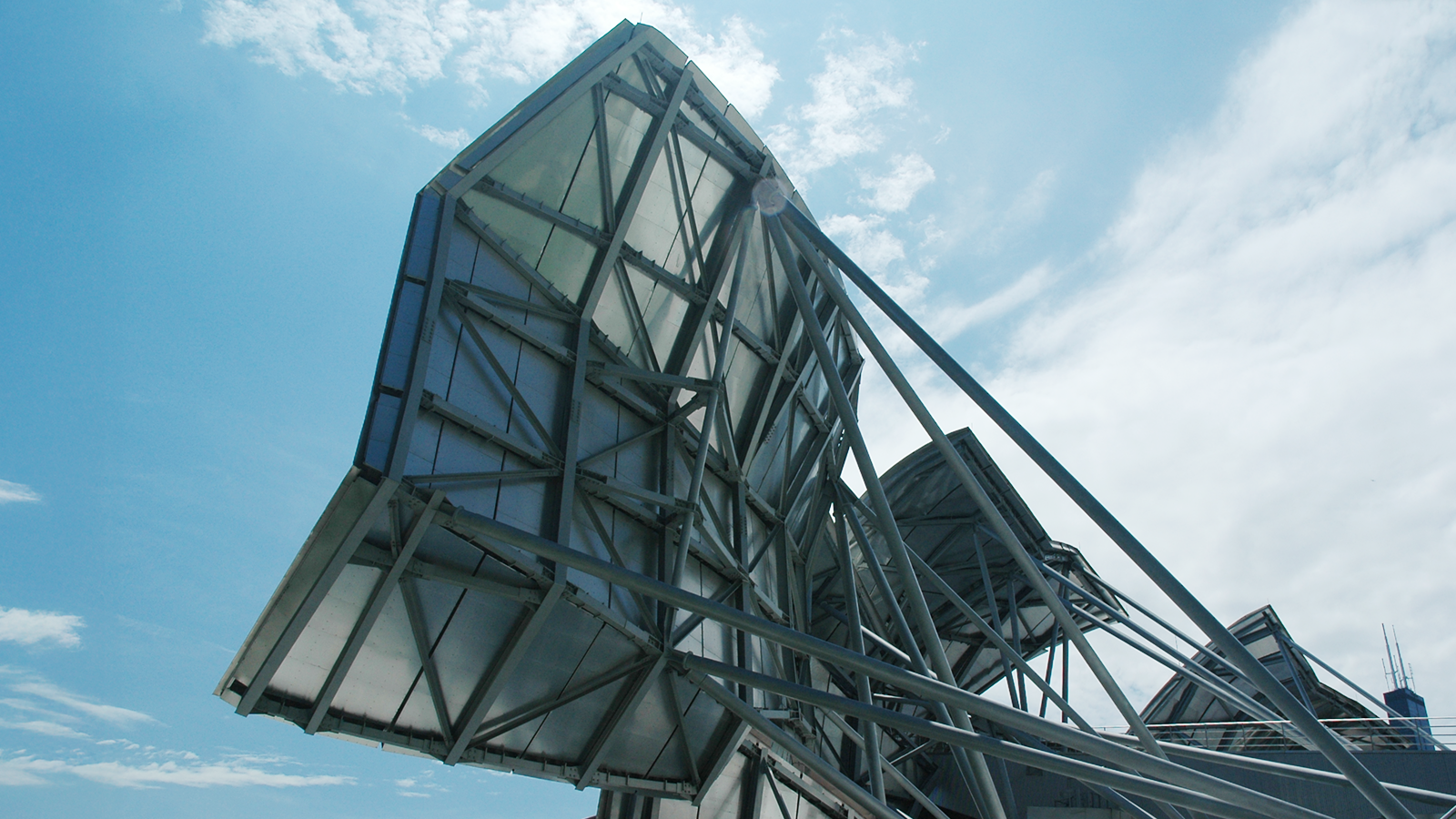

The backside of Gehry’s Pritzker Music Pavilion in Chicago

The architect Frank Gehry passed away earlier this month on December 5th. His death came just a little over a week after the death of Robert Stern, who himself shuffled off this mortal coil on November 27. This has been a rough year for this particular generation of famous architects as both Ricardo Scofidio (of Diller Scofidio + Renfro) and David Childs (formerly of SOM) both died in March.

In thinking about the passing of these individual architects, it’s also worth acknowledging that the era of the “starchitect” as a meaningful concept has come to an end. This portmanteau lacks a formal definition, but it’s generally understood to refer to an architect whose fame has “crossed over” such that their identifiable body of work has become know to the wider public. Gehry was a poster child of this status: ask a non-architect to name an architect, chances are they would list Frank O. Gehry immediately after listing the other famous Frank architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Gehry’s playful use of materials and increasingly-complex sculptural forms made his work destinations in themselves. His 1997 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, for example, almost single-handedly transformed a declining industrial city into a cultural destination. The “Bilbao effect” became a term used to describe how investment in a conspicuous building project could produce an outsized economic impact on its host city. In his imperial phase, Gehry designed everything from private residences to concert halls and skyscrapers. As an index of his fame, he appeared in animated form on The Simpsons and was satirized on the pages of The Onion. For better or worse, his designs became something of a status symbol, with institutions and individuals alike wanting to add a “Gehry building” to their campus or portfolio.

Although I was never a particular fan of his particular approach to architecture, I did respect it. When commercially-available computer-aided design software lacked the sophistication to describe his project’s complex curvilinear geometries, his office created software of its own (famously adapting the aerospace engineering platform used to design fighter aircraft). For me, I was always drawn to the interaction between the smooth, sculptural skin of his buildings with the “messy,” engineered structure required to support it.

Whether due to the demise of the monthly architecture magazine or the fact a shared monoculture no longer exists, there seem to be no starchitects rising to take the place of people like Gehry. Then again, this last generation of famous architects may have hastened the demise of that category.

For all the admiration I had for the technical proficiency of the work produced by his office, I do worry that Gehry’s work (or at least his fame) was having a deleterious effect on architecture as a profession. A member of the general public might visit a museum designed by Gehry or see a photo of one of his buildings in a news article. They might come away thinking, “That’s cool!” They might be impressed by the spectacle and maybe even consider it “beautiful.” But somewhere along the way a chasm fromed between the “great architecture” of someone like Gehry and the “regular building” where most people live and work. By spending decades focusing on the former, surprisingly little has changed for the latter. Most of us do not live in homes influenced by Frank O. Gehry, but that cannot be said of the other Frank. Whether it be open floor plans, slab foundations, or carports, many familiar elements of American homes today were pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright.

And that is why when you ask a non-architect to name an architect, they always list the other Frank first.