Return to Framlingham

My daughter and a volunteer from the Parham Airfield Museum study the site where a B-17 crashed in 1944 (overlaid)

Earlier this month I had the opportunity to return to the small market town of Framlingham in Suffolk, England. I say “return” because I first visited this area northeast of London some 25 years ago. As an architecture student participating in a summer study abroad program, I had spent a month traveling throughout the United Kingdom looking at historic buildings. I extended my stay to look for some of my own history: specifically, to visit the airfield where my grandfather had been stationed during the Second World War.

Back before everyone and everything had a presence on the internet, I didn’t know what I would find. I had located the former airfield on a physical map (Google Maps wouldn’t exist for another six years) and took a train to Ipswich and a bus to Framlingham before walking the final four miles on my foot. To my surprise I found that not only had the control tower been restored, but that it contained a museum dedicated to the 390th Bombardment Group that was stationed there. Within that museum were fragments of the plane my grandfather had been flying when he crashed northeast of the airfield in 1944.

A grainy 1999 photo of the display containing fragments from my grandfather’s crashed B-17

I’ve referenced that crash and my visit to the museum before, but during this most recent trip I had the opportunity to visit the site of the crash itself. One of the museum’s volunteers generously drove us there and together we attempted to reconstruct the specifics of what happened by referencing a handful of photographs taken the morning after the crash. It was moving to stand along the brick wall featured in the photos and imagine a four-engine heavy bomber careening towards it.

In the weeks after returning home, I continued researching the incident (a surprising amounts of information is available online) and spoke with several legitimate experts (including a B-17 historian and a pilot who flies B-17s for the Commemorative Air Force) to try and answer some of the questions I still had. Given the event in question happened over 80 years ago and the fact that I’m neither a World War II historian nor an aircraft accident investigator, some of the details may not be entirely correct, but I feel I’ve assembled a reasonably accurate narrative describing what likely transpired just after midnight on April 12, 1944:

My grandfather, Lieutenant Isaac Leslie Hightower, was the co-pilot of a crew that had just completed training in the use of a specialized B-17 equipped with a primitive radar system that would allow targets to be located when they would otherwise be obscured by clouds. On the evening of April 11th, he and the rest of his crew were ordered to fly one of these “PFF” B-17s back to their home base so it could be used as a pathfinder on a mission scheduled for the following day. As a result, the aircraft was loaded with 2,800 gallons of fuel, four 500-pound bombs, and two extra ground crew “passengers” in addition to its standard 10-man flight crew. (McLachlan, 59-60)

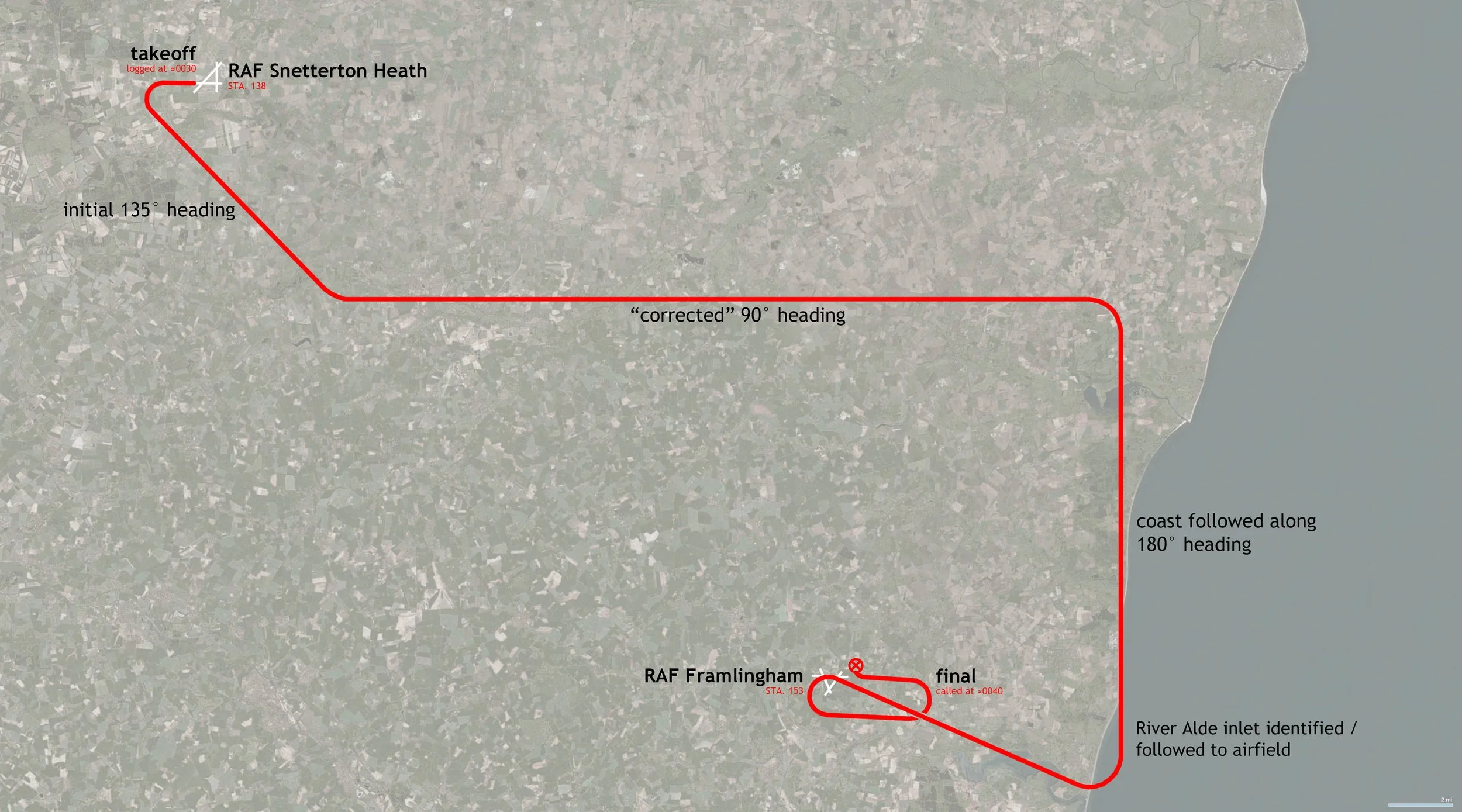

They took off at 12:30am, but due to a navigational error, ended up taking a somewhat indirect route to its destination, covering a distance of about 50 miles from takeoff at RAF Snetterton Heath until contact was made with RAF Framlingham (the airfield was actually closer to the town of Parham, but as “RAF Parham” sounded too much like the nearby “RAF Marham” so the name was changed). The winds were blowing in the from west to east that particular morning, so the B-17 set up for an east-west landing on the airfield’s main runway. A witness near one of RAF Framlingham’s hangars would later report seeing a bomber fly overhead on its downwind leg "followed by a darkened, twin engine machine he did not recognize." (McLachlan, 61)

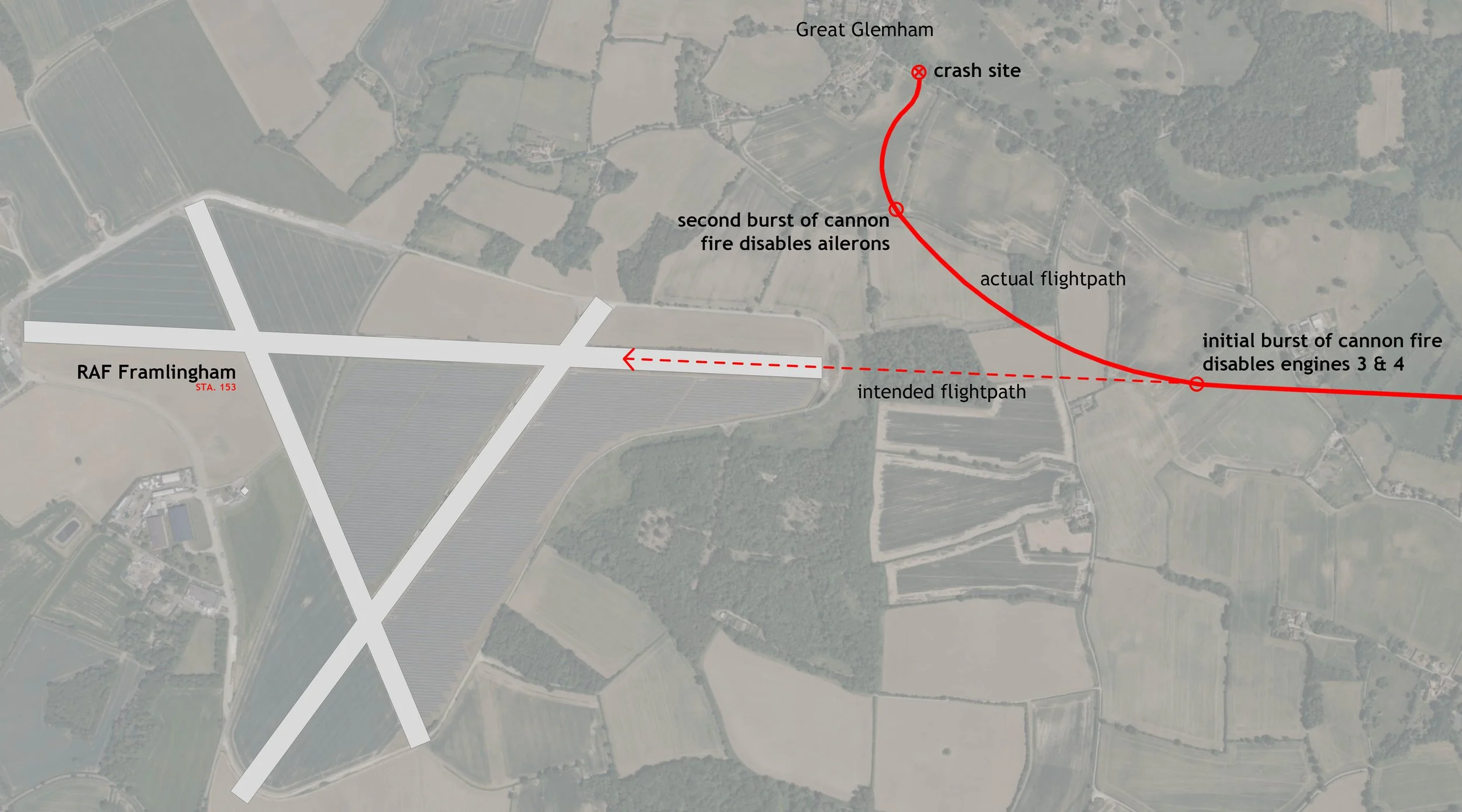

A Halifax bomber crew downed by the same Luftwaffe crew a few weeks later described how by "approaching the returning bombers from below, flying level, but below, they could then tilt the mid-fuselage machine guns upwards and fire directly into the unprotected underbelly of the bomber." This appears to be what happened here as well. The control tower at RAF Framlingham logged that the B-17 "called up for landing instructions while on final approach at the height of approximately 200 feet," and it was sometime after this that the German Me 410 that had been trailing it opened fire. (Leivers, 174)

Lieutenant Donald MacGregor, the pilot who would have been seated beside my grandfather, thought their aircraft was being mistakenly targeted by the airfield's anti-aircraft batteries. He reacted to the initial burst of cannon fire by aborting the landing and throttling all four engines. However, as engines 3 and 4 had been knocked out, that action only increased the asymmetrical application of thrust and caused the plane to turn and roll right. (McLachlan, 61)

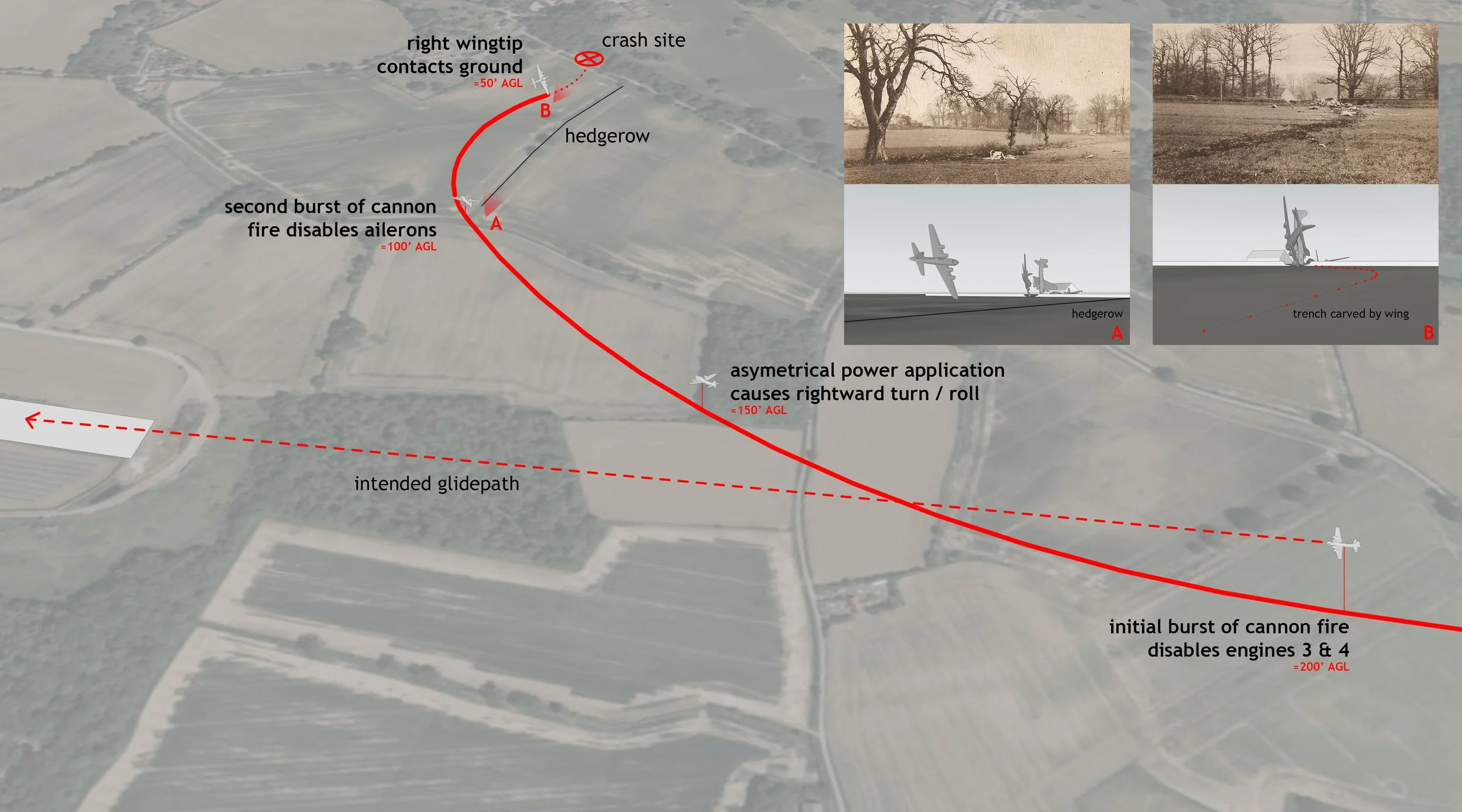

A moment later, a second burst from the Me 410 caused additional damage and blew open a hole in the cockpit and tore off its windshield. Having lost a portion of the right wing and the aileron control that went with it, the B-17’s roll continued until what remained of the wing contacted the ground in the field to the south of New Road.

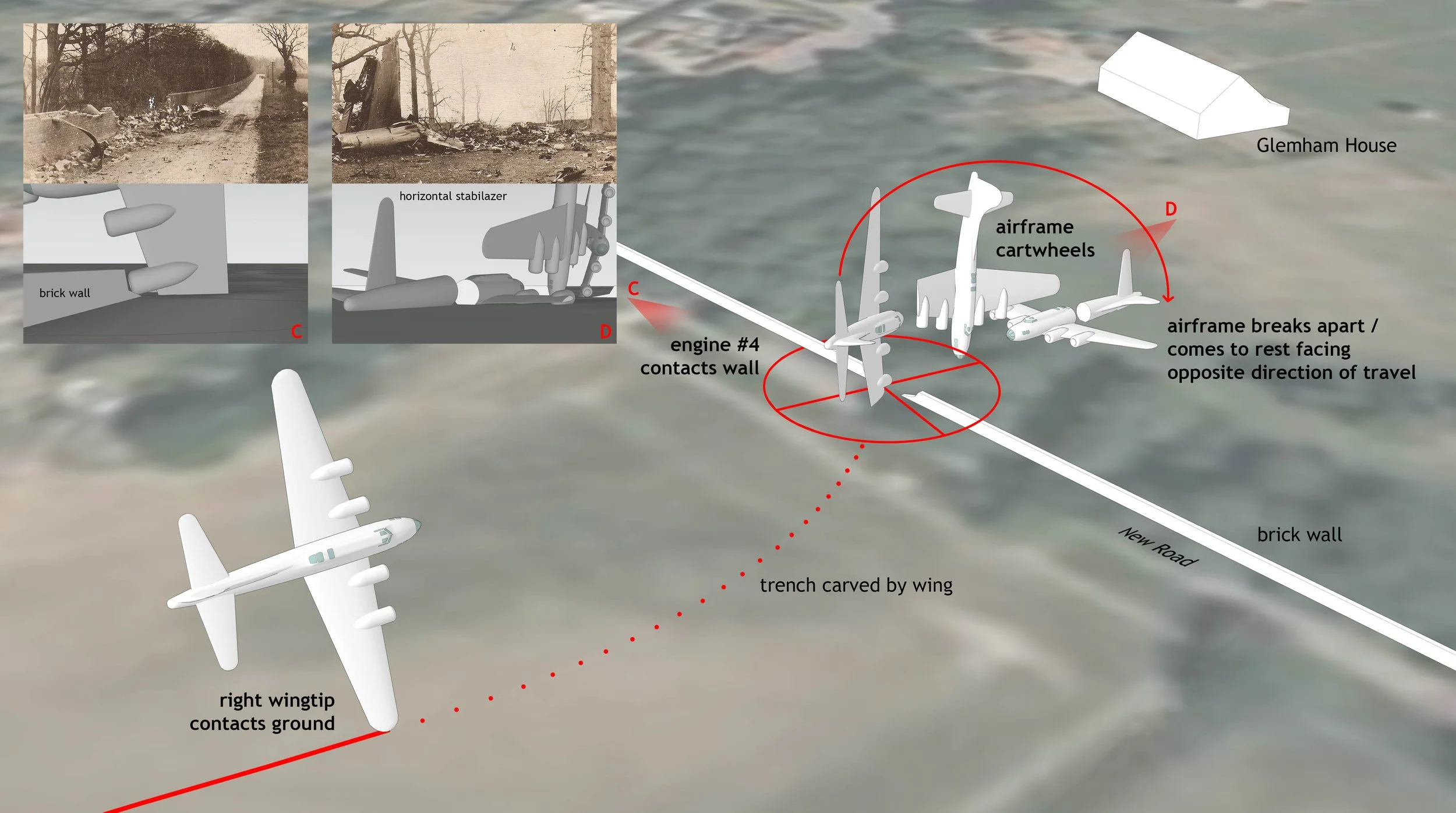

The bomber was in an extreme bank at this point which explains the relatively narrow swath of damage to the surrounding trees caused by an aircraft with a 103-foot wingspan. It seems reasonable to assume that the #4 engine nacelle clipped the brick wall running along the north side of New Road, blowing open a hole in that wall (while also explaining how a propeller came to rest on the opposite side of the wall from most of the wreckage). It also seems likely that the collision of a particularly massive part of the plane - such as an engine - with a particularly rigid structure on the ground - such as a wall - caused what remained of the airframe to "cartwheel" over its nose before coming to rest pointing in the opposite direction from which it had traveled.

Given the earlier damage to the cockpit and the fact air crews rarely wore the primitive lap belts installed in B-17s, both the pilot and my grandfather were ejected from the tumbling plane. This, ironically, may have ensured their survival as most of the crew members in the front half of the aircraft (the bombardier, navigator, and radio operator) perished in the crash. (McLachlan, 62) Despite the ferocity of the impact, neither the fuel nor the bombs initially exploded. This allowed the surviving members of the crew to walk (or be pulled) to safety before the fires that had been ignited set off the bombs. The resulting concussion shattered windows in the nearby village of Great Glemham and “sent a pillar of flame flashing 300 feet into the night sky.” (McLachlan, 63)

As fascinating as the details of my grandfather’s crash - and the fact eight people survived it - may be, they’re not particularly exceptional. Stories like this (and many that ended much more tragically) occurred every day the Eighth Air Force flew. Later on the same day of my grandfather’s crash, for example, B-17s from RAF Framlingham and other airfields across eastern England set out on the previously planned mission to bomb the aircraft manufacturing centers of Leipzig, Germany. But because the target was obscured by clouds - and because the radar-equipped pathfinder plane had been shot out of the sky earlier that morning - the mission had to be aborted and none of the 455 bombers that took off dropped any of their explosive payloads on the intended target.

Even so, 6 bombers were lost and 12 men were killed with an additional 56 listed as missing in action when their planes went down over enemy territory. (Mission 085 Synopsis)

The details of their stories are no less interesting or worthy of being told than my grandfather’s: the only difference is the grandchildren who might have penned them were never born. They were never able to return to where their grandfathers almost perished because circumstances aligned such that they did die in the noble fight to free Europe of tyranny.

McLachlan, Russell J. and Ian and Zorn Eighth Air Force Bomber Stories: Eye witness accounts from American Airmen and British Civilians in the Second World War. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens, 1992.

Leivers, Roger, Stirling to Essen: The Godmanchester Stirling: A Bomber Command Story of Courage and Tragedy. Stotfold: Fighting High, 2017.

Mission 085 Synopsis, “390th Missions Database”, www.390th.org.